Police Career

After getting married and furnishing their home, Lester Loomis had only about $20. At the time he had the use of a steam driven saw, and he went door to door selling a cord of wood for a dollar. He was making about $25 a day, but he had heard that workers were in demand in the booming city of Los Angeles.

He traveled to Los Angeles in early 1887, the trip by train through Sacramento and Oakland taking three days, while his new wife Grace stayed in Reno. He planned to find work as a plasterer, the family trade. He carried with him a letter of introduction to banker L. N. Breed, vice-president of Southern California National Bank, who was also President of the Los Angeles City Council.

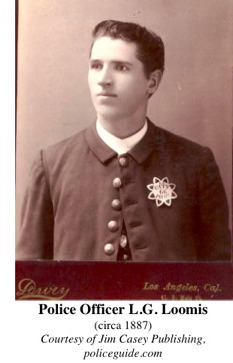

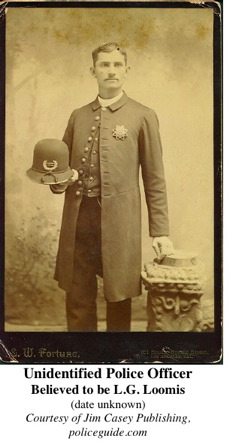

Upon arriving in town, Loomis went straight to Mr. Breed's office. Mr. Breed told him that plasterers in the city were unionized, and that it might take a long time to find work. He suggested instead that Loomis join the police force. After discussing Loomis' previous experience as a law officer in Nevada and California, they went to meet Police Chief John Skinner. In March, 1887, Lester became a special officer in the Los Angeles Police Department. The following month he was appointed a regular officer.

During the early days of his police career, he happened to stop a man in a buggy who was speeding through the intersection of Temple and Main streets. This happened on subsequent days, until a bystander informed Loomis that the man in the buggy was the Mayor of Los Angeles. Concerned, Loomis went to Breed's office and asked if he knew Mayor. Breed, a close friend of Mayor William Workman, took Loomis into a back room; there sat the Mayor. The young Loomis began stammering out an apology, but Mr. Workman stopped him, saying "I wish every man on the force were like you." Workman quickly developed a respect for Loomis that lasted throughout his time on the force. On September 8, 1887, Loomis and W.T. Jeffries were appointed sergeants, the first in the department.

Corruption was also a problem in the department. Gambling within the city was common, and the gambling houses regularly paid off some members of the force to avoid being raided. Mayor Workman took office on a reform platform, pledging to rid the city of gambling and other undesirables, and to clean up the police department. His reform efforts peaked during the administration of Chief Thomas J. Cuddy, who took office on January 23, 1888.

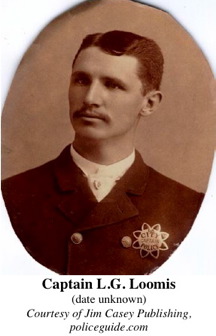

Mayor Workman often relied on Loomis as a man of integrity that he could trust within the department. Shortly after his promotion to sergeant, Workman and Breed had given him instructions to investigate gambling and red light activities. This created friction between Loomis and his Chiefs, first Darcy and then Cuddy. On May 10, 1888, despite the objections of Chief Cuddy, Loomis was appointed Captain of Police, second in command to the Chief. His appointment was intended to support the effort to clean up the department and rid the city of gambling.

Chief Cuddy was given direct orders by the Police Commission to suppress gambling and remove undesirables from the city, orders which he refused to obey. In July, 1888, Chinese gambler Wong Que accused Cuddy of taking money to protect gamblers and of releasing prisoners for personal reasons. An investigation was instigated, culminating in an August report to the Commission condemning the Chief and calling for his dismissal.

Thomas Cuddy reacted to the report by bringing charges against Loomis, accusing him of taking bribes and undermining the department. Few believed the accusations, and the Police Commission quickly determined the charges were false and found Loomis innocent of any wrongdoing.

Politics again entered the debate over Cuddy, and action on the investigative report was repeatedly delayed. Finally, on September 24, amid increasing pressure from citizens and the media, Cuddy resigned, and vacated his post the next day. Mayor Workman assumed responsibility for the department, and placed Loomis in charge of the force. Loomis immediately ordered all gambling houses closed, a situation that prevailed during Loomis' time as Acting Chief.

When Loomis was asked to become the permanent Chief, he stipulated that he would only do so if he was granted autonomy to do the job free from the political manipulations common in the past. Lacking that, he said he would rather remain as Captain under a new Chief.

On October 1, 1888, Hubert Benedict was appointed Chief, a position that he held until January 1, 1889, when the new administration of Mayor John Bryson came into office. During these three months, it appears that Loomis was effectively in charge of the department, while Chief Benedict handled the political side of the job.

Los Angeles approved a new city charter late in 1888, resulting in the installation of a new government in March, 1889. Mayor Bryson was replaced by Henry Hazard who appointed a long-time friend, J. Frank Burns, as Chief. Burns, who according to Loomis ran a gambling house in town, took advantage of the police department shuffle that accompanied each change of administration, and immediately fired Loomis.

Burns proved to be an unpopular Chief and in July, 1889, he was replaced by J. M. Glass, Loomis was immediately reinstated to the force. Chief Glass proved to be one of the departments most successful Chiefs, holding the job for almost twelve years.

Captain Loomis, tired of the insecurity and politics of police work, left the department on August 31, 1889, to become superintendent of Evergreen Cemetery, a job he would hold for fourteen years. His LAPD police career lasted only 2-1/2 years, but left an indelible mark; he would be known as Captain Loomis for the rest of his life.

[Initial Version 02/01/07]

[Sources: Lester Loomis Journals, LA Times]